By Tate Williams

Read and share the article on Inside Philanthropy.

A major challenge to organizing and advocacy around climate change is how even to approach a problem so large, complex, and gradually advancing (although it feels less gradual with every year, to be honest).

An advocacy group that launched in 2014 has one answer—we respond like we’re at war.

For the Climate Mobilization Project, the climate crisis demands not incremental changes or gradual reductions in emissions, but an emergency response led by government that is on the scale of the response to World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The group just picked up a grant from the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Shelter Rock of $100,000, an amount they say is the “country’s single largest philanthropic investment in emergency climate action.”

This modest grant from a local funder to a little-known climate outfit is worth a closer look, with an eye to takeaways for other players in this space. We’ve been saying for a while now that if climate change is really the time-urgent, existential threat that so many, including top funders, say it is, then civil society and philanthropy needs to start acting on that belief. Nonprofits need to hit harder and foundations need to give more—a lot more—while there’s still time.

But what would that look like, exactly?

The Climate Mobilization Project was started by a group of friends from varying backgrounds—psychology, journalism, neuroscience—and now boasts an advisory board that includes former executive director of Greenpeace International, Paul Gilding, and leading climatologist Michael E. Mann.

The project’s director, Margaret Klein Salamon, told Inside Philanthropy that the grant from UUCSR was the first that it had ever received. “We have been funded thus far through monthly giving, major giving, and especially the in-kind donations of volunteers,” she said. “We have leveraged volunteers, including experts in policy, climate science and organizing, to a huge degree.”

The war-footing for climate change concept is more than just a rallying cry. It’s an operational approach that’s gotten increasing attention in recent years. For example, a 2016 NBER paper by Hugh Rockoff explored the rapid transformation of the U.S. economy in World War II to see whether this mobilization model “provides lessons about how the economy could be transformed to meet scarcities produced by climate change or other environmental challenges.” Bill McKibben also fleshed out the World War II analog in a long 2016 article in the New Republic, noting that Pearl Harbor made “individual Americans willing to do hard things: pay more in taxes, buy billions upon billions in war bonds, endure the shortages and disruptions that came when the country’s entire economy converted to wartime production.”

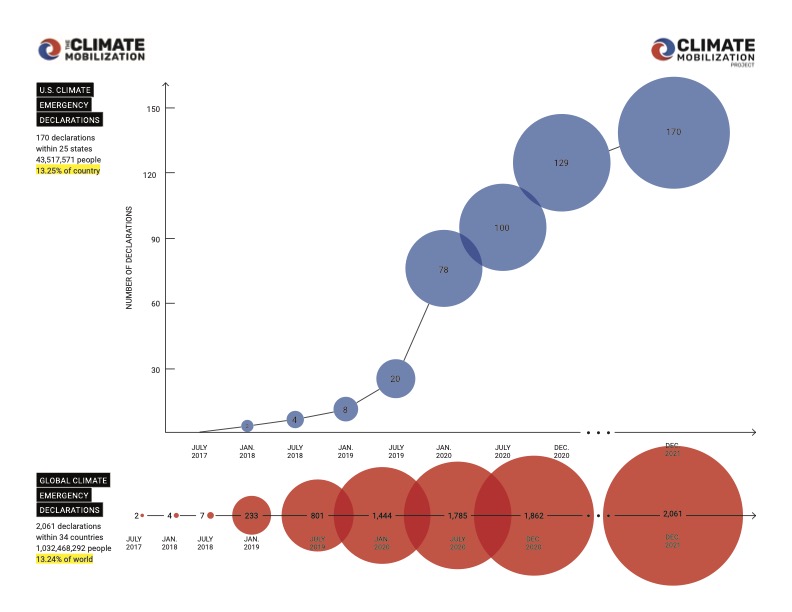

For its part, the Climate Mobilization Project is following a city-by-city strategy to move the country into emergency mode. It’s campaigning to get governments to declare a climate emergency, initiate aggressive carbon reduction commitments, and become advocates for further emergency mobilization. The campaign cites some political advances, including the Los Angeles City Council voting to explore what would be the country’s first Climate Emergency Mobilization Department. And just this week, Berkeley, California, declared a climate emergency.

The people behind it aren’t fixed on one particular pathway for cities to take, but a proposed plan for how the country might proceed is pretty intense, including a transformation of our food systems, government rationing, carbon sequestration research, massive land preservation, and significant reductions in resource consumption. The group also has a strong environmental justice framing, calling for an “emergency speed transition that not only seeks to prevent unimaginable suffering from climate and environmental catastrophe, but reinvents our economy to address the social inequities on which an extractive economy is based.”

That’s likely a big part of what connected with the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Shelter Rock. UUCSR is a prominent congregation based in New York with a long record of social justice work and philanthropy. In addition to its Veatch grantmaking program, a Congregational Large Grants Program gives amounts of $100,000 to grantees voted on by the congregation. A climate change grant is a unique choice for the program, although past giving is wide-ranging, from prison reform to disaster relief.

The compelling thing about the Climate Mobilization Project is that, while arguably unrealistic in its goals—since there’s no political consensus on this issue, as Rockoff’s paper notes—it is unflinching in its diagnosis of the level of response that climate change warrants. Much of its goal is to build a movement around how we should collectively think about climate change—mainly that the status quo of the approach to date is unacceptable. And from the standpoint of a funder like UUCSR, it’s a status quo that’s certainly unjust.

Read and share the article on Inside Philanthropy.