(Reposting from the Council Action in the Climate Emergency (CACE) Blog)

Bryony Edwards (Updated on 8 May 2019)

As climate emergency talking and thinking shifts further towards climate emergency action, it is imperative that ‘climate emergency’ is not co-opted to mean something ‘convenient’ or ‘pragmatic’ (ie. weak goals and slow action). Climate emergency has to stand for safe climate principles for restoring a safe climate.

So what should climate emergency emissions targets look like? This blog attempts to draw a line in the sand, proposing how to set targets for both central governments and councils.

Where are we today in the climate emergency campaign?

In the space of 5 months, the phrase climate emergency has become household. Several months ago, the hashtag #climateemergency appeared in two tweets a week from a handful of the usual suspects. A snap count now shows 80 odd tweets in the past 30 minutes, including from mainstream voices.

For the last few weeks, 1000s with Extinction Rebellion are blocking central streets and bridges in London, demanding that their government implement a climate emergency response.

Just a few weeks ago, The Australia Institute released findings from a nationwide survey that the majority of Australians believe we face a climate emergency and want to see a ‘climate emergency’ response including the type of ‘mobilisation of resources undertaken in WWII’. The fact that we are hearing this language from any mainstream institution is a paradigm shift. These majority findings were found across different party persuasions.

As of today, the phrase, climate emergency’ is used by:

-

The UK, which passed a non-binding opposition motion at the beginning of May. Wales and the Scottish National Party declared earlier in the week.

-

Over 500 councils across seven countries having declared a climate emergency (Aust, US, UK, Canada, Switzerland, Italy and Germany) with many more councils in the pipeline.

-

Universities; the University of Bristol and University of Newcastle recently declared

-

School Strikers

-

The Club of Rome, an international organisation with members including eminent scientists, business leaders, ex-politicians and retired heads of state.

-

14 MPs in Australia of different stripes

-

Political parties, including the UK Labour Party and Scottish National Party

-

Wales, which has declared a climate emergency

-

Large environmental organisations, which have just now adopted the term.

What does climate emergency actually mean?

An emergency response is prioritised, urgent, whole-of-government, outside of business-as-usual action with short timeframes. To climate campaigners it may mean any of these 3 things:

-

a program to deliver maximum protection of all people, all species and civilisation, globally

-

a program to deliver the Paris Agreement 1.5 degrees target fast, and increasingly

-

an acknowledgement that current levels of warming and future trajectories are already catastrophic and we need to take urgent action to avoid this future scenario – understanding that where we end up will not be not a good place.

While there is no automatic single meaning for climate emergency, people using the term should understand that

-

We are too hot now. Our inaction over decades has set off positive feedback loops that speed up global warming. This means targets decades out are suicidal; we need to start now and we need to do it as fast as is humanly possible.

-

At current emissions levels (400+ppm CO2 / 470ppm+ CO2 equivalents) we have already built in 25m+ of sea level rise. All atolls are estimated to be unliveable by 2050, not to mention other low-lying coastal areas.

-

Ecological collapse across numerous systems; too many to name here. Credible news sites and scientific sources cover the seriousness of the issue.

Because we have an extremely dangerous climate now and switching to a zero carbon society still leaves us with today’s carbon in the atmosphere plus what will be emitted between now and the day we achieve the zero-carbon goal, zero carbon is not a safe end target.

As such, we need to go to negative emissions to restore safe (pre-industrial) greenhouse gas concentrations (safe at about 280-300ppm) and restore a safe climate. Getting to negative emissions ASAP means:

-

Zero emissions across all sectors as fast as possible

-

To begin drawing down excess greenhouse gas emissions on an industrial scale using available strategies and investigating new strategies. We don’t know how long it will take but using current land based tech (revegetation, soil carbon, biochar), it may take over 100 years.

-

Create an immediate cooling. At present with current particulate pollution levels, we are geo-engineering almost 1 degree of shade (solar reflection). If the world went to zero emissions today, the global average temperature would jump half a degree Celsius or more.

While these 3 demands are a tall order and extremely ‘inconvenient’, there’s a high chance anything less is giving up on a liveable planet and our futures.

If we are not very clear with our expectations, it will not happen:

-

If we don’t demand emergency speed transition to zero emissions across each sector, it will not happen.

-

If we don’t demand industrial scale drawdown, it will not happen.

-

If we don’t demand economic restructuring toward a safe climate, this response will not happen.

A climate emergency response goes way beyond not doing more bad stuff, it also means doing more good stuff than we ever thought possible to restore a safe climate.

What is the original intended meaning of climate emergency?

Among different campaigners, early uses of the term ‘climate emergency’ may have varied it with the intention of safe climate restoration at emergency speed.

From a Australian perspective, dedicated grass-roots climate campaigners started using the term at least as far back as 2008 (eg. in Climate Code Red) to represent what was needed to restore a safe climate. The expression was used 26 times in this linked article from 2013. ‘Climate Emergency’ was formalised in May 2016 with the Australian ‘Climate Emergency Declaration’.

The thinking for what climate emergency in action looked like was based on work of organisations like Centre for Alternative Technology (UK) and Beyond Zero Emissions, (Aust) in the mid 2000s. Urgent sector wide transition plans.

In the US, the term appeared at least as early as 2011. It was probably The Climate Mobilization that popularised the term.

No doubt there were other earlier uses of the term so apologies if these uses have not been captured. More detail on the history of climate emergency is available here.

Is everyone talking climate emergency use the safe climate restoration frame?

No! For example, there are councils passing climate emergency declarations that are aiming for net zero by 2050; this includes large councils such as the London Assembly and Vancouver.

After declaring, London quickly went on to approve another runway at Gatwick. Although the UK made a ‘resolution’ for a climate emergency, Labour and Tory Councillors in Cumbria went on to back a new coal mine.

The UK’s Committee on Climate Change (the CCC), an independent, statutory body established under the Climate Change Act 2008, has recommended just ‘zero by 2050’ for the UK’s emergency response. The CCC is similar to Australia’s Climate Council, which recommends the same target for Australia.

It shouldn’t be surprising that soft targets are defeatist. Soft targets set us up to fail.

What is the role of targets?

Governments usually set targets before the full suite of how they will be achieved is known. As such, they tend to set targets for complex work far into the future. But decades-out targets can be easily ignored because any one government can’t be easily held to account on them.

A target ideally works as a slogan of 3 to 5 words, and needs to communicate ‘what we need to do and how fast should it be done’. The target can also include more detail, such as interim or contributing targets, which can hold any single government to account.

Given the scope of work for a climate emergency response, once adopted, a climate emergency target should drive policy development, governance and performance measurement across all of government’s work. The target implicitly communicates the degree of priority the work will need, which in this case is maximum priority.

There are good arguments for not providing a target deadline in case it is too ambitious and stakeholders expect failure, but this is outweighed by the benefits of having a timeframe (or the cons of not having one). And with the right governance, more will be achieved with an ambitious target than with a less ambitious one.

A recent example of a target at work is Oxfordshire Council (UK). At the time of writing this, Oxfordshire Council is trying to weaken the target they set with their climate emergency declaration (zero by 2030). The council is worried they won’t meet the target. Perhaps not but having such an ambitious target means the council will have to go above and beyond to try to meet it.

When setting goals for safe climate restoration, it is implicit that these goals will require:

-

Immediate implementation of current solutions and seeking other solutions via R&D

-

A restructure of governance and the economy to achieve those goals.

Because we have to demand the action needed first then it’s important we get the targets right. Our governments will latch onto the easiest around and then may fall short of them anyway. Governments will look for a path requiring the least amount of effort, whereas we need a herculean effort.

A brief history of climate target setting

We are currently grappling with a very climate-confused public not only due to years of misinformation from hard climate deniers, but also misinformation from the soft climate deniers, generally the large environmental organisations, who are supposedly representing a safe climate but present weak targets for governments.

People trust in these environmental organisations so they trust the targets of ‘zero by 2050’ that they promote. Hence the general confusion around what a safe target is. Ask a random person whether zero by 2050 is safe climate policy and they’ll probably say yes.

If we are too hot now, how can net zero by 2050 save us?

Why have environmental organisations set weak targets?

Environmental organisations set weak goals because they wanted to be taken seriously by government, but in addition they have:

-

lacked imagination in what can be achieved

-

misread what the public is ready for.

The environmental organisations should have been asking themselves, ‘how do we get the public on board to drive an effective campaign with government?’, not ‘what will government accept?’.

In private conversations, staff from these environmental organisations confide that the goals they are setting ‘couldn’t save us’ but they ‘don’t want to frighten people away’. These eNGOs have effectively given up and have created havoc in their wake.

This environmental organisation campaigning logic was a bit like trying encourage locals to stay and fight an oncoming bushfire by lying that the fire is 200km away, when in fact the fire is already throwing embers and all roads out are closed. Which would you imagine to be more effective at motivating to stay and fight the fire? The eNGOs chose the 200km option. Jane Morton’s booklet, ‘Don’t Mention the Emergency?’ examines this campaigning dissonance in detail.

If the environmental organisations had been campaigning on safe climate goals for the past few decades, we would be in a very different place today with regard to public understanding and what they demanded from government. Yes, the hard deniers would still be around but we wouldn’t be dealing with such a high degree of public confusion on what we need to do.

What are the risks if we couple climate emergency with suicidal targets now?

Just in the past week, two large environmental organisations have finally woken up to the fact that ‘fear’ is in fact a necessary tool for climate campaigning and have declared a climate emergency. These same eNGOs had refused to use ‘fear’ in climate campaigning for years. ‘Climate emergency’ as a term was officially blacklisted by professionals campaigning for climate action.

As with the past so with the future. If the organisations with the biggest profiles and deepest pockets couple the ‘climate emergency’ headline with soft targets, nothing will have changed other than the word ‘emergency’ and the broader public will believe they are in good hands.

environmental organisations’ inability to shift into emergency mode has just been confirmed by WWF. WWF has jumped on the ‘emergency’ bandwagon with their declaration last week but only moved their ‘net zero’ target forward five years from 2050 to 2045.

And these decades-out targets are what governments will adopt, regardless of what is actually possibly under a mobilisation response with technical breakthroughs that mobilising economies can drive ahead of the deadline.

Most governments will do all they can to compromise emissions targets. Climate campaigners supposedly campaigning for a safe climate shouldn’t do it for them.

Reject suicidal targets from any group speaking on behalf of the planet and promote safe climate targets!

Maximum protection

Philip Sutton, Co-Author of ‘Climate Code Red’ has stated that ‘We need a step before setting the goal of restoring a safe climate. Restoring a safe climate is a means to an end – providing protection so the first question is who and what are we trying to protect? Why do we want to protect them? For ethical reasons or because they are a means to protecting something else? And how secure do we want that protection to be?’

Philip’s view is that we should aim to protect all people, species and civilisation globally and we should aim to protect the climate vulnerable. He calls this ‘maximum protection’.

I would imagine this idea of maximum protection is instinctively the view of most climate campaigners.

To provide maximum protection we need to do two things:

-

restore a safe (pre-warming) climate

-

make the transition with the least loss of people and species/biodiversity.

Climate-emergency target setting

We need to set targets based on what can be achieved under ideal circumstances (ie emergency action), not business as usual or a supposedly pragmatic view on what our current political landscape can deliver.

Beyond Zero Emissions have shown that 10 year transition to zero across most sectors is possible but we can probably do much of it faster.

High level targets for central governments

What we need to capture in a high level target is three main components:

-

Zero emissions by 2025-2030 (or 5-10 years from announcement) plus

-

Begin industrial scale drawdown of excess greenhouse gas emissions, e.g. Large scale drawdown of emissions annually

-

Investigate the best options to create an immediate cooling

But how to turn this 3-part target a slogan of 5 words or less? These could include:

-

Zero and drawdown by 2025

-

Negative emissions by 2025

-

Zero and drawdown by 2030, zero by 2025

If implemented globally it could be ‘A cooler planet by 2025’ or ‘a safe climate by 2030’

Targets for Councils

A council target is more complicated because many councils lack regulatory and economic levers to achieve net zero or net negative emissions.

Councils should acknowledge:

-

the central government target above (whether or not the central government has set it as a target or is working to achieve it), plus

-

a target that reflects the the council’s community wide goals across the council and community portfolio. This could still be ‘the largest possible negative emissions as soon as possible’.

In addition, the council can state what they will do or achieve across each sector that is within their control. In the declaration, these targets could be captured as, for example:

-

Restoring healthy tree canopies and wetlands across all available green spaces within 10 years

-

Zero or negative emissions in council waste management within 5 years

-

300% increase in the capacity of private solar PV across the community in four years.

(See the CACE website for ‘CACE goals and targets fact sheet’ (under development as at 5 May 2019) and Nuts and Bolts for a range of options across council portfolios.)

Last word

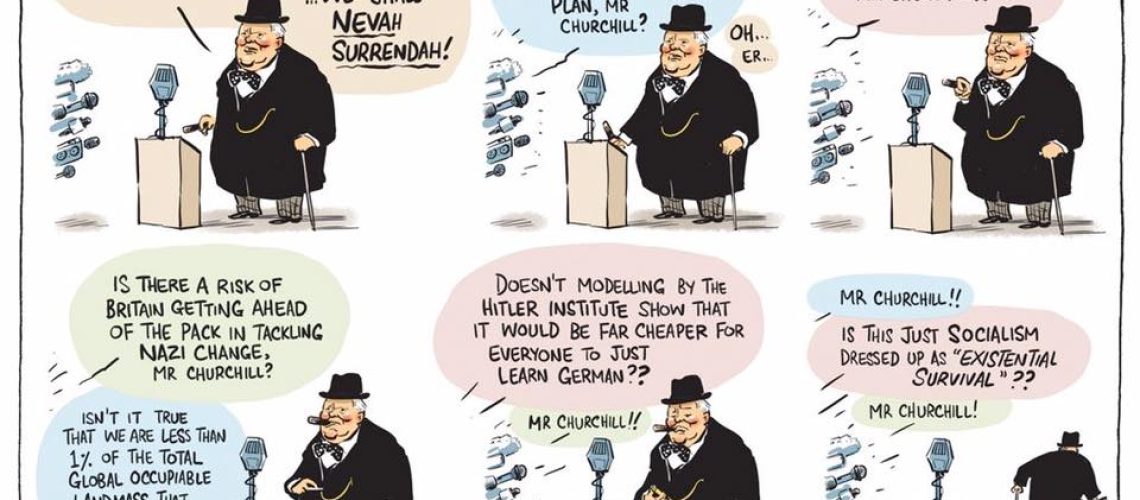

It is amazing what can be accomplished in emergency mode (Eg UK in WWII) when government realigns to achieve something ambitious, when the public is properly informed, when vested interests are forced to stand down.

If this is our last ditch effort at saving the planet, why would we comprise safe climate principles before we’ve even sat at the government negotiating table? Compromising on safe climate principles is how we got here in the first place.